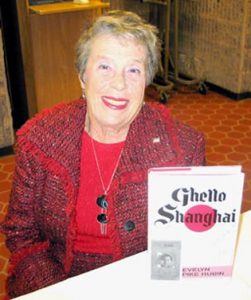

Evelyn Pike Rubin: Jewish Activist, Author, and Lecturer

Evelyn Pike Rubin, Jewish activist, author and lecturer, was born in Breslau, Germany, where her ancestors had lived for many generations. Evelyn’s parents were raised as strict orthodox Jews, a tradition they passed on to their child at a young age. Evelyn was a descendant of Yeheskal Landau, Chief Rabbi of Prague from 1753 to 1793. Her grandfather was a Talmudic scholar. After he died in 1911, Evelyn’s mother started her own paper business to support the family. By the time she married in 1929, she had a flourishing business with dozens of clients throughout Germany. Evelyn, who was born just before Hitler came into power, only remembers Germany as one led by the Nazis. After the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, German anti-Semitism escalated. Jews were restricted from schools, parks, and many restaurants and businesses. As a result Evelyn could not continue her swimming and ice skating lessons. She reminisces, “it was a very strange feeling since the other children were being allowed to go in, and I didn’t think I looked different from anybody else. All of a sudden I was not allowed to participate.”

Evelyn Pike Rubin, Jewish activist, author and lecturer, was born in Breslau, Germany, where her ancestors had lived for many generations. Evelyn’s parents were raised as strict orthodox Jews, a tradition they passed on to their child at a young age. Evelyn was a descendant of Yeheskal Landau, Chief Rabbi of Prague from 1753 to 1793. Her grandfather was a Talmudic scholar. After he died in 1911, Evelyn’s mother started her own paper business to support the family. By the time she married in 1929, she had a flourishing business with dozens of clients throughout Germany. Evelyn, who was born just before Hitler came into power, only remembers Germany as one led by the Nazis. After the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, German anti-Semitism escalated. Jews were restricted from schools, parks, and many restaurants and businesses. As a result Evelyn could not continue her swimming and ice skating lessons. She reminisces, “it was a very strange feeling since the other children were being allowed to go in, and I didn’t think I looked different from anybody else. All of a sudden I was not allowed to participate.”

On November 9 and 10, 1938, during Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) synagogues were burned all over Germany. Jewish shops were shattered, and thousands of Jewish men were arrested and sent to Nazi concentration camps. Evelyn’s father hid in his Christian landlord’s attic, but was later arrested while trying to fetch Evelyn from a friend’s home. He was sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp for three weeks. Evelyn remembers asking her mother what a concentration camp was. She was told it was like a prison. “I wondered why my father was in prison; he didn’t do anything wrong. My mother explained to me, ‘[it was] because he’s Jewish.’ I could not understand what was wrong with being Jewish. I was brought up to be a proud Jew. We were different from the other Germans because of the way we observed, but we were German the same as they were German. Unfortunately, not everybody looked at it that way.”

In 1939, at the age of eight, her family fled Germany to the only refuge available to them—Shanghai, China. She attended the Shanghai Jewish School, a British-run Jewish school. As Evelyn tells it, “I went to school with Polish Jews, with Russian Jews, with Hungarian Jews, with Jews from Iraq who were born in Shanghai. For us kids, we were all the same. Of course, for those of us coming from Europe, we did have one thing in common because none of us spoke English. We all had to learn a foreign language together. Maybe that’s what made for the camaraderie. My Shanghai classmates and I still correspond and remain in touch to this day. I have very good memories of our school days together.”

For Evelyn’s mother, however, Shanghai was a harsh place. The Shanghai ghetto was established in 1943, and ruled by the Japanese, who forced all Jewish refugees to live in the Hongkew slum, in their case in extreme poverty. Evelyn reflects, “How horrible it must have been for her to think, ‘I don’t have food for my child.’ If you had no parent to take care of you, either you scrounged on your own or you disappeared. Unfortunately, there were those who disappeared or died of disease. I feel the Shanghai experience is a little publicized story because, as terrible as it was, we were the lucky survivors. I didn’t have to look over my shoulder, fearful of being dragged to the gas chambers or gunned down in the street. We lived in comparative freedom. Our ghetto was not a European ghetto. I’m alive because of the Japanese, and I’m grateful. They saved my life!”

At the end of the war in 1947, Evelyn emigrated to the United States, eventually settling in New York and Long Island. The inspiring story of Evelyn’s childhood growing up in Germany, her survival along with more than 18,000 Jewish refugees in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, China, during World War II, her immigration to America and subsequent life on Long Island is chronicled in her memoir Ghetto Shanghai. “When everything seemed hopeless, there was an open door. I don’t want anyone to forget where that door was,” says Rubin. “That is why the story needs to be told. Soon there won’t be anyone around to remember how we survived against all odds. . . . I survived in order to carry on the tradition and to teach my children what it means to be a Jew.”

Dedicating most of her adult life on Long Island to Jewish causes, she was Vice President for Social Action of the Jericho Jewish Center and served on many boards. She is past president of her temple sisterhood and the Center’s Hebrew School Parents’ Council. Evelyn lectured on the Holocaust and immigrant Jewish history at area schools, synagogues, and organizations. She passed away in April 2022. She will be missed.